The (Im)possibility of Plants in Exhibitions

C-PLATFORM × Yasmine Ostendorf

Project Description

I get a phone call asking if I’m interested in purchasing some greenery for “a very good price.” A local contemporary art space is selling legions of tropical plants that were part of an exhibition attempting to re-create an Amazonian rainforest – an endeavor where the moist, damp, sticky and deafening wilderness of the Amazon is supposed to take our breath away in the middle of the European winter. My curiosity is triggered because it sounds rather presumptuous. The description of the exhibition includes: “Once you’re inside, there is no escape. The pressure of the environment is so powerful and hypnotic that it propels people into a dreamstate.”

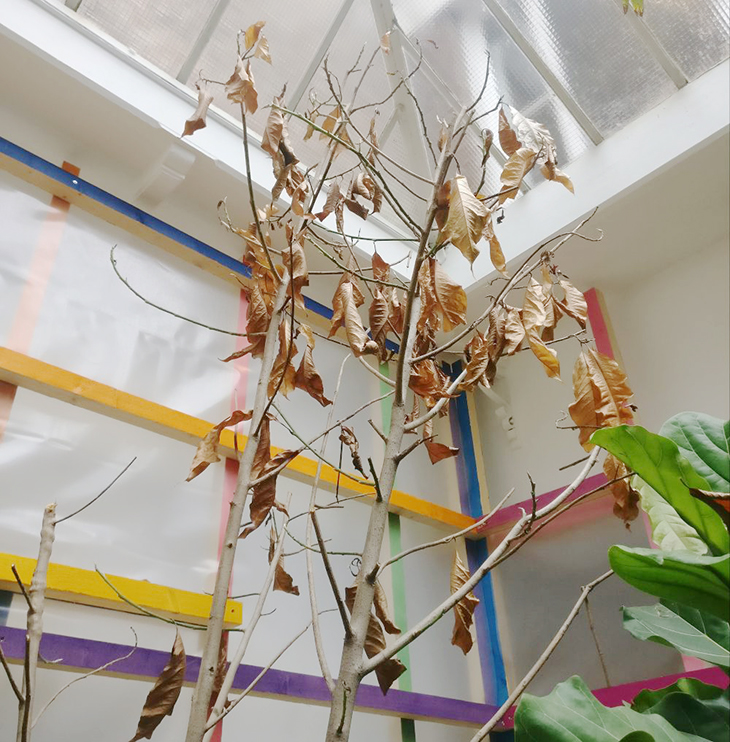

It sounds very enticing and dreamlike but when I enter the space a few months later, it is more akin to a nightmare: the local Amazonian rainforest is a battlefield of dead plants. I wonder how it was ever a good idea to put plants with different temperature and humidity needs next to each other, let alone import tropical plants to a gallery space in February. I am told that when the plants arrived it was minus five degrees Celsius outside and the plants’ soil was frozen – a problem that was solved by pumping up the heat (and carbon emissions). These tantalizing forces of the jungle were clearly dreamed up with little understanding of the plants’ needs, presenting us a with a naive and romanticized notion of nature. Do we really want to raise awareness of the Brazilian rainforest’s declining ecosystems by creating a slowly dying ecosystem in a gallery space? It would be ironic if it weren’t so sad.

I am excited about the desire from artists and art spaces to address environmental challenges, but using plants in cultural spaces often proves problematic. We’re all familiar with the iconic image of the half-dead palm tree in a corner of the theatre, there to fill and freshen up the stage during the Q&A. Cultural spaces are designed to make the art and artists look good, and air-conditioning and lights are always going to favor the art over the plants.

In search of better practices, I consulted artist Ju Hyun Lee working with Ludovic Burel as the duo KVM. Though their practice is very much rooted in (art)theory – Timothy Morton’s Hyperobjects: Philosopy and Ecology after the End of the Worldbeing a central reference – their most recent work currently exhibited in Tubology – Our Lives in Tubes in Dunkirk, France, includes edible plants. They have grown 75 varieties of hot peppers and 21 varieties of edible tubers, marrying them with the art and design collection as well as the architecture of the FRAC Grand Large. The duration of the show (April-December) reflects the bio-rhythm of the plants. Just like farmers, the artists started early in the season, meeting and engaging with local gardeners, using the heated surfaces in their greenhouses to germinate chili peppers. Growing chili pepper in early spring in the north of France proved a challenge. The artists brought in many experts including Bernard Dupont, who succeeds in growing hundreds of varieties of peppers near Besançon, and ethnobotanist Jean-Claude Bruneel, who is studying wild plants in the era of climate change.

Even with all this gardening expertise at hand, there were more barriers to overcome. The exhibition space, like most exhibition spaces, is designed for “non-living artwork,” meaning there are plenty of protocols about temperature and humidity levels. This created a conflict of interest between the living and non-living artworks. The protocols were designed to conserve the art collection, not to maximize the plants’ wellbeing. What conditions were needed to have both living and non-living artworks successfully co-habit?

Art institutions are not prepared to deal with art that is alive and needs permanent care. While the bulk of the work usually takes place before the opening, living artworks require ongoing care. Plants need to be watered, aired, and given proper treatment. The first week of the Tubology show, midges appeared because the enriched organic soil had not fully decomposed. The second week, the chillies suffered from an attack of aphids due to accidental overwatering. The show had to close in order to clean and treat the hot pepper plants, but the artists were adamant about re-opening again. After covering the chillies with protective sheets, they engaged the local community – including chefs, gardeners, and botanists – and the staff to help solve this problem. Ju Hyun states: “Animals, including snails and insects, are a common problem familiar to gardeners. In the industrial agriculture world, these vegetable-eating creatures are considered the enemy, fought with chemical weapons. But there is no need to panic; there is a wide range of natural remedies out there, including black soap and nettle manure.

The gallery staff had to step out of their comfort zone and the process of looking after the plants became a binding force between different parties. Ju Hyun adds: “We will certainly have more issues to face together. Growing plants indoor is not ideal. The attention and care they require is the most important part of our work. Artists and art institutions have to invent a successful model for the ecological transition of the art world. We believe living artworks can help. Our society largely relies on division of labor and delegating, but today’s ecological urgency asks us to take responsibility towards living things – humans, plants, animals and the planet.”

It is interesting to bring the notion of collective care and responsibility into the exhibition space. We need to recognize the layered complexity of the discourse around ‘Nature’. With ecosystem collapse, species extinction, climate change and other environmental issues becoming more pressing, artists all over the world are responding and creating exhibitions that include plants and other living things. However, good intentions or spectacle do not contribute to this discourse nor make interesting exhibitions. We have to remain aware of the complexity of ecosystems as well as the associated dialogues, realizing that if the artwork is alive, it can also die.

Related Information

Yasmine Ostendorf / NL

Curator Yasmine Ostendorf (MA) has worked extensively on international cultural mobility programs and on the topic of art and environment for expert organizations such as Julie’s Bicycle (UK), Bamboo Curtain Studio (TW) Cape Farewell (UK) and Trans Artists (NL). She founded the Green Art Lab Alliance, a network of 35 cultural organizations in Europe and Asia that addresses our social and environmental responsibility, and is the author of the series of guides “Creative Responses to Sustainability.” She is the Head of Nature Research at the Van Eyck Academy (NL), a lab that enables artists to consider nature in relation to ecological and landscape development issues and the initiator of the Van Eyck Food Lab.

At the moment, She is organising a Food Art Film Festival on the Future of Food. See flyer below.

https://www.janvaneyck.nl/nieuws/food-art-film-festival/

Image credit © Artists & Climate Change

Date

2018年8月30日

Category

Future Institute