Space as Substance: Beyond the Scenic Hudson

C-PLATFORM × Matthew Friday

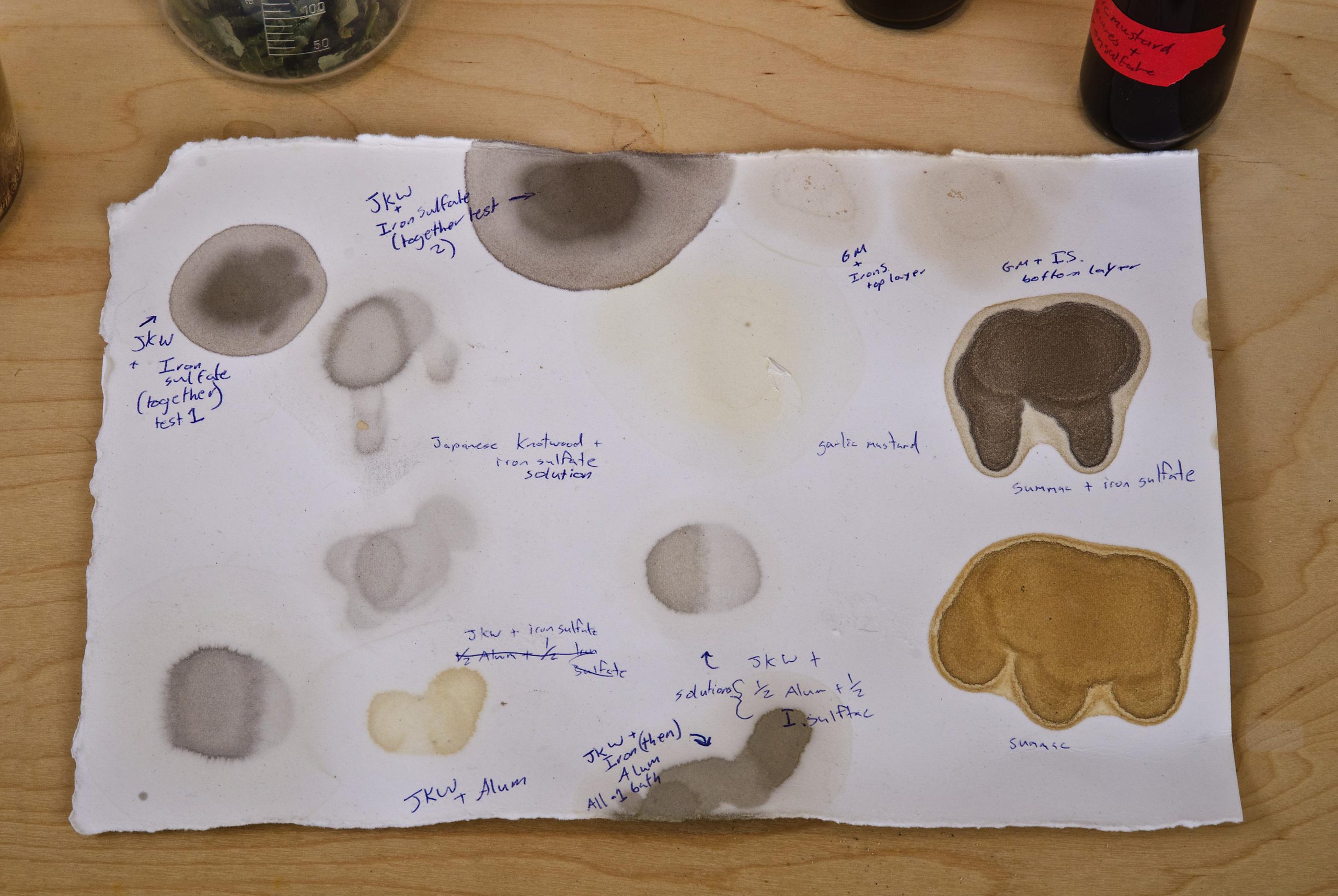

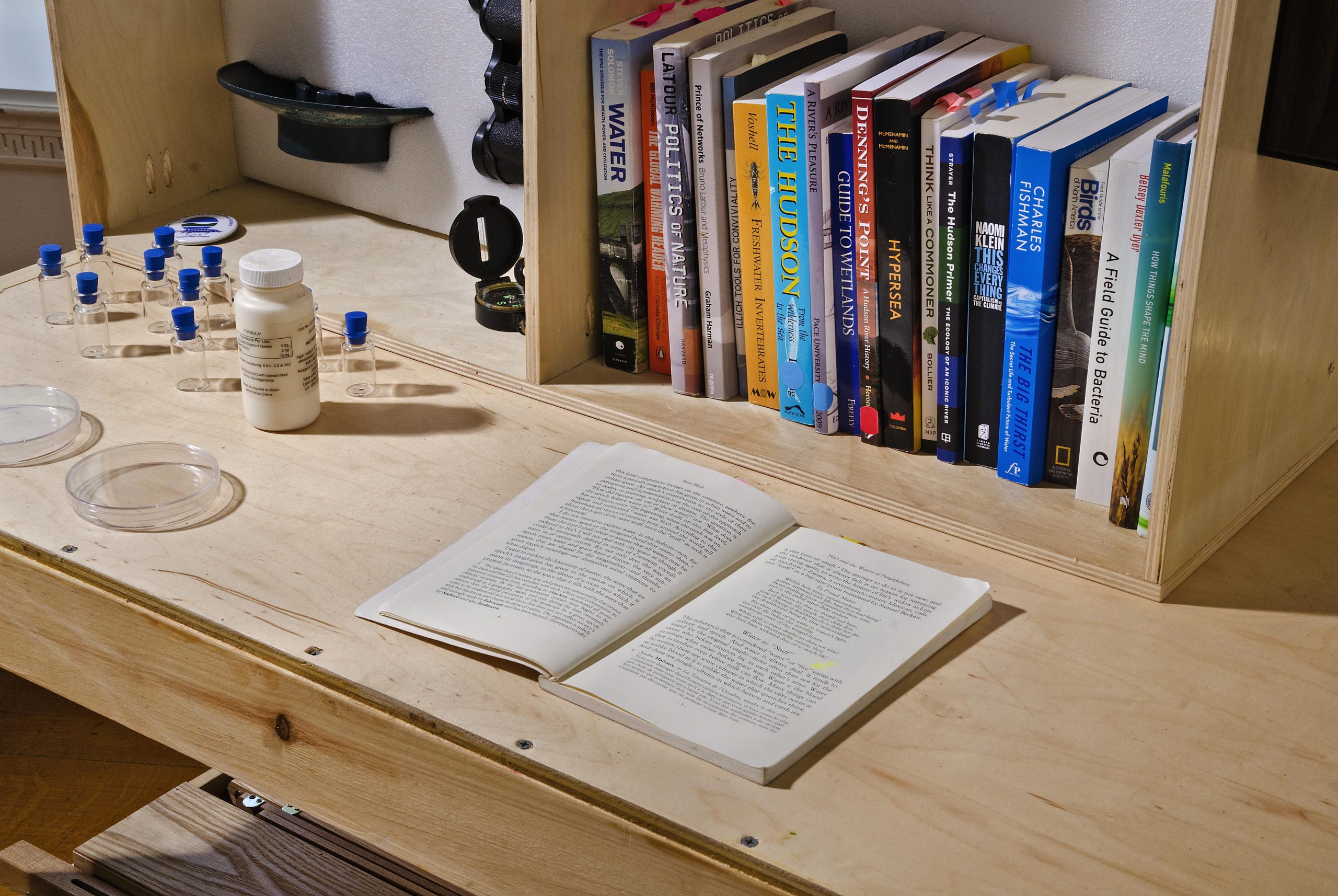

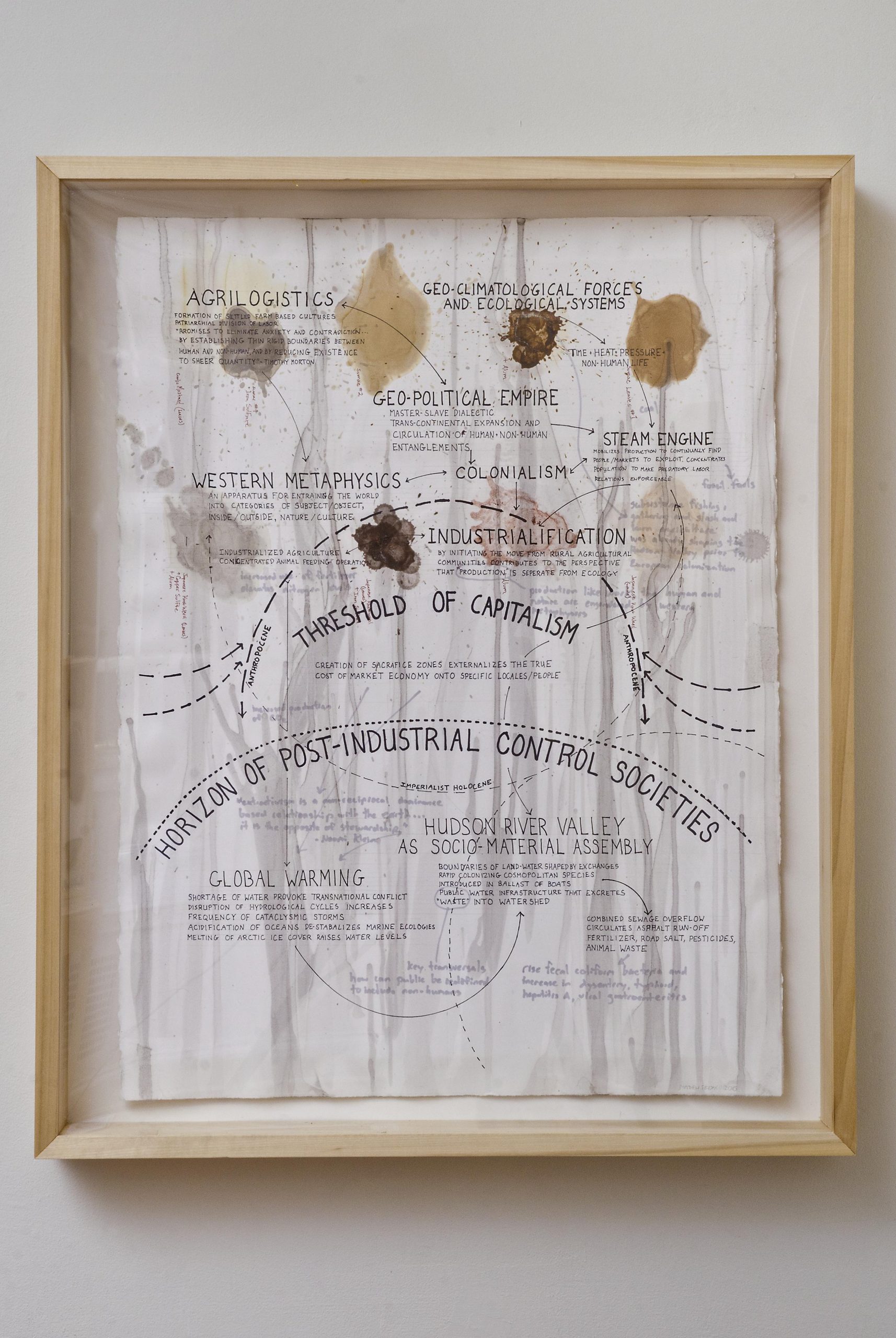

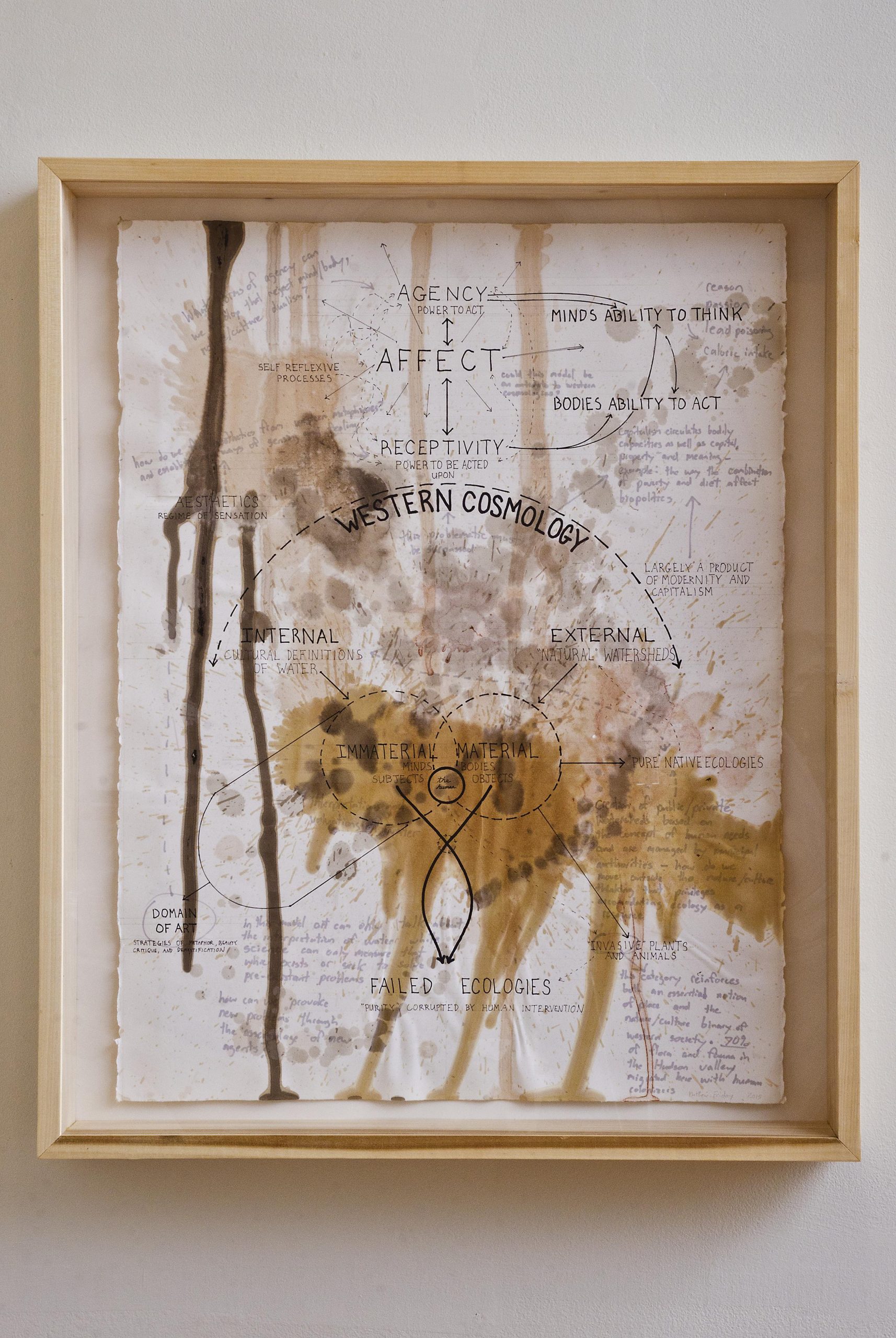

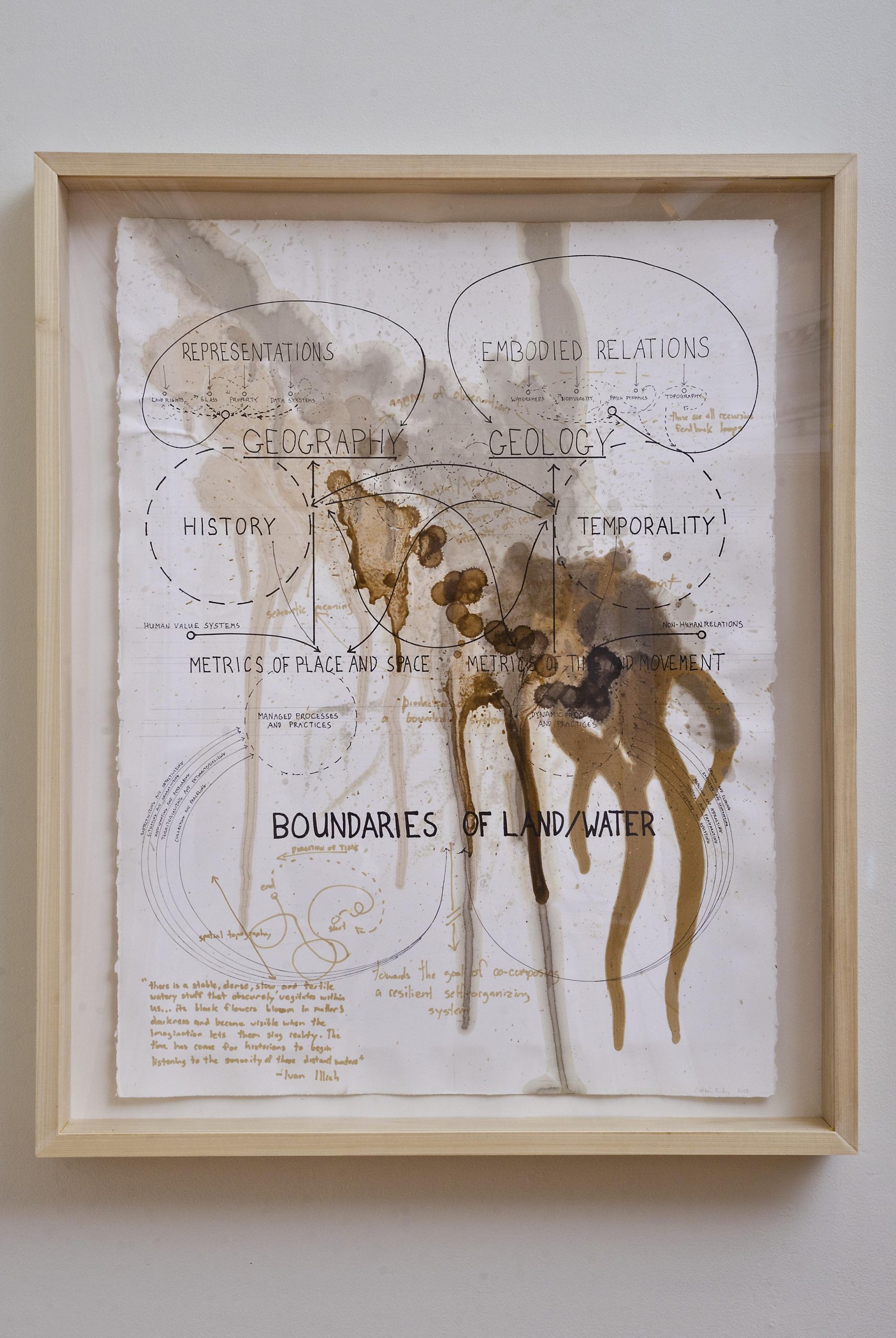

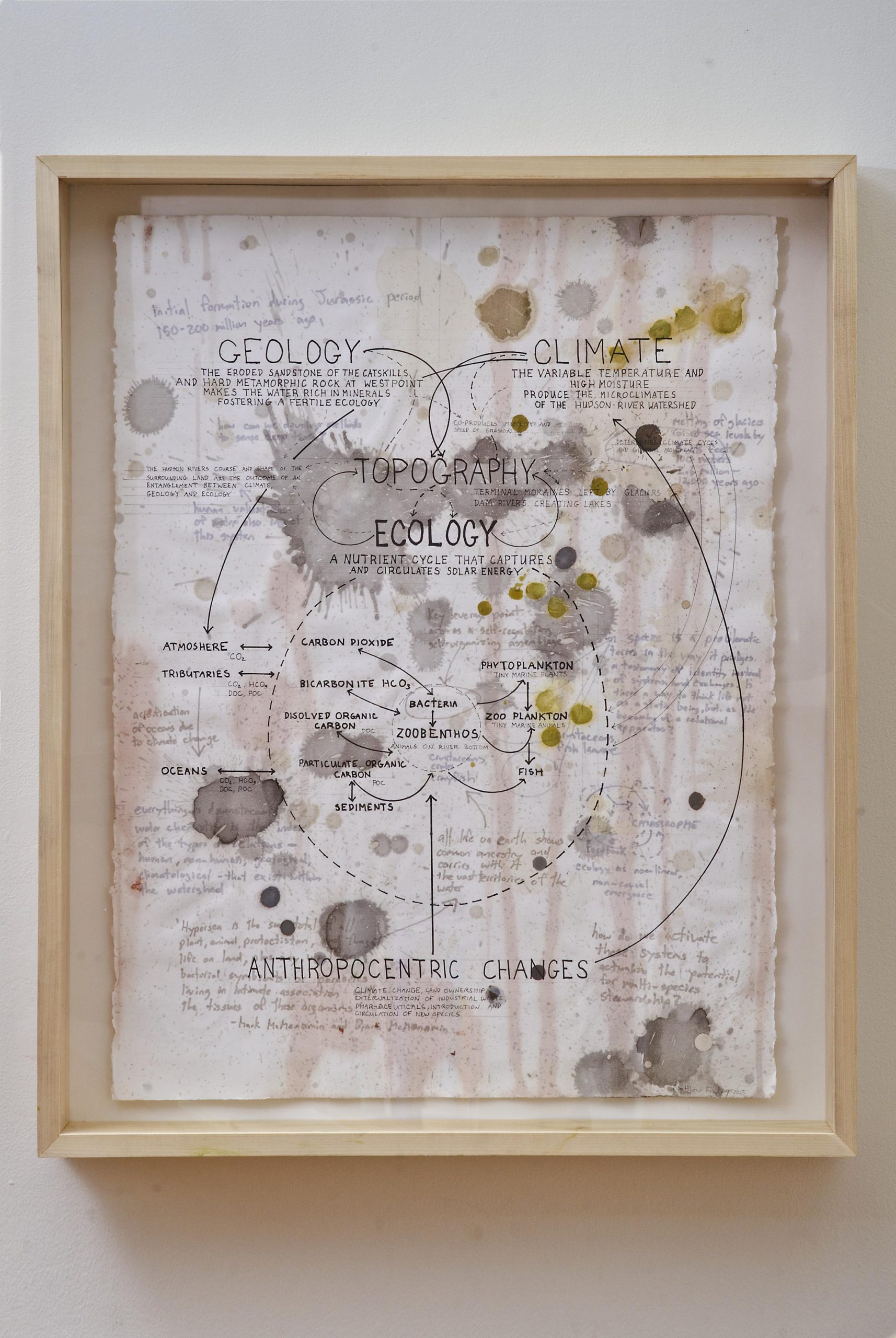

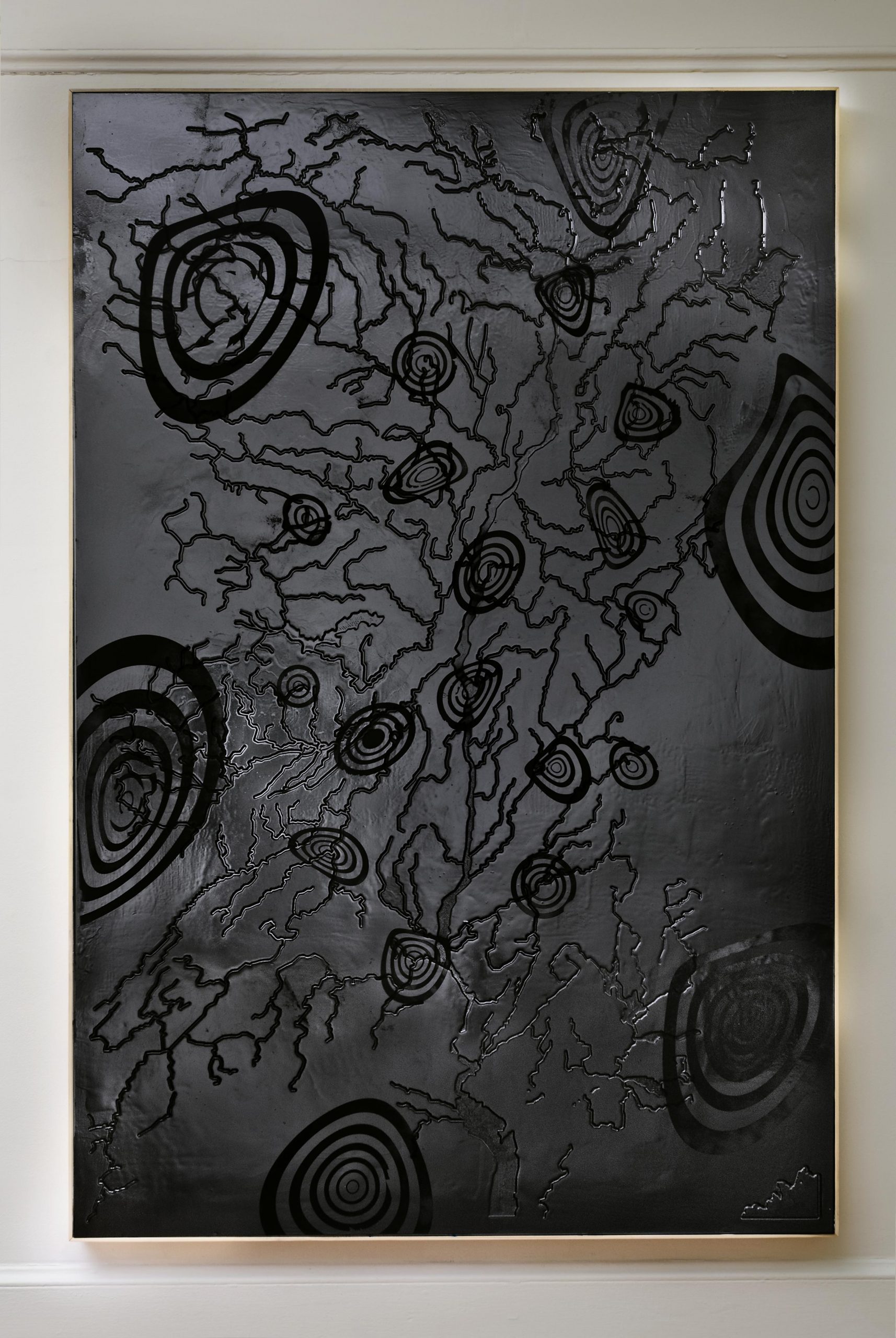

Through his expansive fieldwork, Matthew Friday poses a question: How can art uncover a different way to relate to ecology, as a thoroughly active partner that demands its own ethics and aesthetics? His search for an answer was mapped through the elements assembled at Wave Hill’s Glyndor Gallery in the Bronx (NY City), featuring the mobile and modular research station that he created as a provisional laboratory and camping platform. Here, it becomes a library and exhibition installation. The station contains a variety of cartographic and scientific instruments for the naturalist/artist, as well as a rocket stove, Fresnel lens, mortar and pestle, water-analysis station, test tubes and books related to watersheds, the Hudson River and political ecology. Friday’s own analysis of the river can be seen in the diagrammatic paintings, overlaying his research and philosophy about the river with information about its health today. To create these paintings, Friday harvests a wide range of plants that play a critical role in the river’s ecosystem, dries them and makes dyes using a sustainably engineered mill that he devised. Using these dyes, Friday has created a series of diagrams that explore species migration, geological and meteorological transformation of the Hudson Valley, as well as ongoing and potential responses to these issues. The large painting is made with remediated toxic mud from General Electric’s dredging sites, combined with coal collected from power plants in the Hudson Valley.

What follows here is a conversation between artist Matthew Friday and Director of Arts and Senior Curator Jennifer McGregor about Friday’s installation at Wave Hill in the fall of 2015.

Q:In this project you pose the following question: how can art uncover a different way to relate to ecology, as a thoroughly active partner that demands its own form of ethics and aesthetics? Is this a question specifically for this project or is in the question that you ask of all your projects? Is there a specific way that you see this project addressing the question that might be new for you?A:As someone with a foot in both the activist and art camps, this question is of particular importance to me. The connection between ethics and aesthetics is at least as old as Plato; it’s only during modernity that we seem to have segregated these two discourses in such a way that conversations about their relationship are particularly impoverished. Activism, which is often presumed to be one of the spheres where the question of ethics shows up, tends to privilege a form of speaking that strives for transparency, clarity and public address and, if there are aesthetics to be considered, they are subordinated to these goals. Conversely, we often take aesthetics to exist solely within the narrow realm of art, where it can be accommodated as entertainment, commodity or critique. Although questions about the relationship between ethics and aesthetics have begun receiving significant attention among contemporary artists, particularly those interested in social practice, I feel like the radical division enacted by modernity plagues our thinking, particularly in regard to how we relate to ecology. For me the question of how matter, in all its mucky glory, shows up became central in thinking about how we model new ways of being in the world. One example of this is the algae dye that was harvested from beds of waterchestnut, a recent and rapid colonizer that with the algae kills off most aquatic life. Creating a production method for this dye meant required understanding the implications this process would have (quite beneficial for fish) on the watershed. In developing paints and papers from local sources, we become accountable to the plants and animals that are also dependent upon them; our health and their health become inexorably linked. For me, ethics unfolds from this increased cycle of situated co-dependence. Q:You employ a collaborative approach to your work, can you talk about the parts of this project that have engages others, such as your students?A:In a very real sense the world itself is collaborative; all of our actions are multiply determined by various forces, institutions and beings. My interest in engaging the watershed derives from a desire to think and act in a collaborative fashion with both humans and non-humans. Just as watersheds are constituted as a vast collections of forces that vary in scale, scope and temporality, so too are humans. For me there is a real pressing need to develop processes that collaboratively engage these collectives and redistributes both agents and agency. The dyes, pigments and paper developed in this exhibition were the result of a partnership with the students at SUNY New Paltz. SUNY New Paltz has a vibrant reputation for ecological research and we are developing ways to sustainably source many of our materials. Additionally, the Hudson Valley is home to a variety of environmental advocacy groups such as the Hudson River Sloop Clearwater, Riverkeeper and the Department of Environmental Conservation. Working with these groups over the past several years, I’ve developed a series of public projects to cultivate environmental literacy and foster ecologically resilient systems and much of that research informs this project. Wave Hill’s unique transdisciplinary pedagogical mission really challenged me to think about how to get people to participate. Including pamphlets that ask people to think about and experiment with their relations to water, the exhibition incorporates numerous tactile and interactive components where people can contribute directly to the exhibition. I’m also excited to be able to offer a plein air landscape painting workshop and children’s art project, both of which engage the questions raised by the project.Q:With regard to the concept of Field Notes, your project references both the sources of information that you draw on (as seen in the library and the photographs) and the methods (the pigment processing mill and other instruments.) Can you talk about the place where the notes meet the distillation into new ideas?A:There is something magical about maps and diagrams; unlike images they don’t present an object but a set of relations. They seem to hold out the promise of radical reconfiguration as if, in their implementation, they could assemble the world anew. When speaking about maps, the philosopher Gilles Deleuze made an interesting point stating, “[…] each map finds itself modified in the following map, rather than finding its origin in the preceding one: from one map to the next, it is not a matter of searching for an original, but of evaluating displacements. Every map is a redistribution of impasses and breakthroughs, of thresholds and enclosures, which necessarily go from bottom to top.” This claim, that maps don’t simply represent things, but rather iteratively build upon existing connections to activate new potentials got me interested in thinking about how this process might be used in relation to ecological systems. The pigment processing mill, plants and energy systems that power it were themselves the result of diagrams that mapped out the ways one could re-assemble a unique association between art and ecology, between people and watersheds. This interplay between map and apparatus is crucial; the entire installation could be understood as diagram that, with participation, co-produces new subjects, ecologies, and politics.Q:Space as Substance: Beyond the Scenic Hudson is part of your ongoing exploration of the Hudson River watershed. How has this particular installation advanced your goals and propelled your inquiry?A:Facing the massive impact of global warming, deregulated power plants, crumbling infrastructure and toxic pollution there is a very real and pressing need to redefine our relations to the Hudson River watershed and much good work has already been done in this regard. Our current political/economic structure – capitalism – presents the world as a set of resources to be used, while externalizing its impact, such as pollution, so that corporations do not have to pay for its true cost. My painting, Pure Color of the Hudson (after Rodchenko), is both a map and index of these forces. Made with polychlorinated biphenyl (PCB) mud obtained from General Electric dredging site and processed waste coal from power plants in the Hudson Valley, it is both an map and index of the radical impact capitalism has had on the watershed. As I developed this piece, I came to believe that just as we need ways to fully visualize this dynamic, we require a way of working that directly challenges our relations of production and thinking about nature as a resource. This installation embodies this search for new alliances, ways of producing materials and modes of sensing the world.Matthew Friday is an educator, writer and transdisciplinary artist whose research focuses on the development of apparatuses and systems that examine and provoke new political ecologies. He has spoken internationally about ecology, aesthetics and politics at venues such as NYU, the Rubin Foundation and Kunsthal Aarhus (Denmark). His essays have appeared in October, the Journal of Modern Craft, the Journal Aesthetics and Protest, the Brooklyn Rail and Art Journal.Working both collectively and individually, Matthew Friday’s projects have taken up issues of urban ecology and watershed remediation. He is an active member of the ecosystem research and design collective SPURSE. He has exhibited at venues including Wave Hill, Spaces (Cleveland), MassMOCA, the Indianapolis Museum of Art, Grand Arts, White Columns, the Kitchen, Bemis Art Center, Kunsthal Aarhus and the BMW Guggenheim LAB. His work has been reviewed in October, the New Art Examiner, Dwell and Art Papers.

Images by Stefan Hagen

Text by Wave Hill, Bronx, New York