C-PLATFORM × Mona Azadian

Project Description

The installation “Being Like a Tree” expresses a lived experience of connecting to nature in reflection on findings from environmental philosophy and ecology. Human empathy and identification with non-human natural elements such as animals, plants, and ecosystems can evoke actions that protect and preserve the environment. Among multiple theoretical understandings of human connection with nature, two concepts led the design process. Some scholars define a connection to nature as developing an “ecological self,” where one sees nature as part of oneself. Alternatively, the connection to nature can be described as an awareness of oneself as a member of a broader biotic community. Referring to these two views, the installation is a conceptual composition presenting human bodies embracing their surrounding natural context.

The work portrays my perception of natural landscapes. As I identify symbolically with nature, I see myself in trees, longing to dance with the flow, becoming unveiled in challenging seasons, contemplating while standing and growing. The initial vision of the work comes from the walks in different natural landscapes, including deserts in the United Arab Emirates and the forests in China. Despite the contrast between the two settings regarding climate and plantation diversity, the sense of relating to the natural elements, particularly trees, was identical. Approaching a free-standing Ghaaf tree within the deserts in Dubai, I felt a sense of admiration, respect, and an urge to unite with it (image 1). On the other hand, it is remarkable that I experienced a similar impulse to merge with the lush setting in bamboo forests in China (image 2). Wandering in a dense labyrinth of trees and seeing myself as a slight pinch in a grand setting provokes ambivalent feelings. I wondered if those trees were a multiplication of me or if I was just a tiny part of a whole. As I could not precisely answer these questions, I looked into them from the deep ecology perspective.

Deep ecologist Arne Naess [1] introduces the concept of “ecological self” and argues that the maturity of the self is not limited to the development of the ego, social self and metaphysical self as defined in modern psychotherapy. He explains that nature, including our immediate environment and our home, is a fundamental part of the developmental phases of the self. As he stresses the process of identification with others as a key to compassion and solidarity, he defines the “ecological self” as a person’s “process of identification”. Based on this idea, further empirical research led by Bragg [2] identifies the condition wherein humans see nature as part of themselves. Another perspective, proposed by ecologist and philosopher Aldo Leopold, suggests seeing a connection to nature as a state where humans view themselves as part of a community that includes non-humans: ”soil, waters, plants, and animals” or collectively the land.”[3]

As I wondered if trees are a multiplication of me or if I was just a tiny part of a whole, I suppose that the positive answer to the first question can highlight the Naess concept of the “ecological self”, where nature is seen as part of oneself. Alternatively, the latter question could relate to Leopold’s idea of relating to nature as a member of a wider biotic community.

Design Process

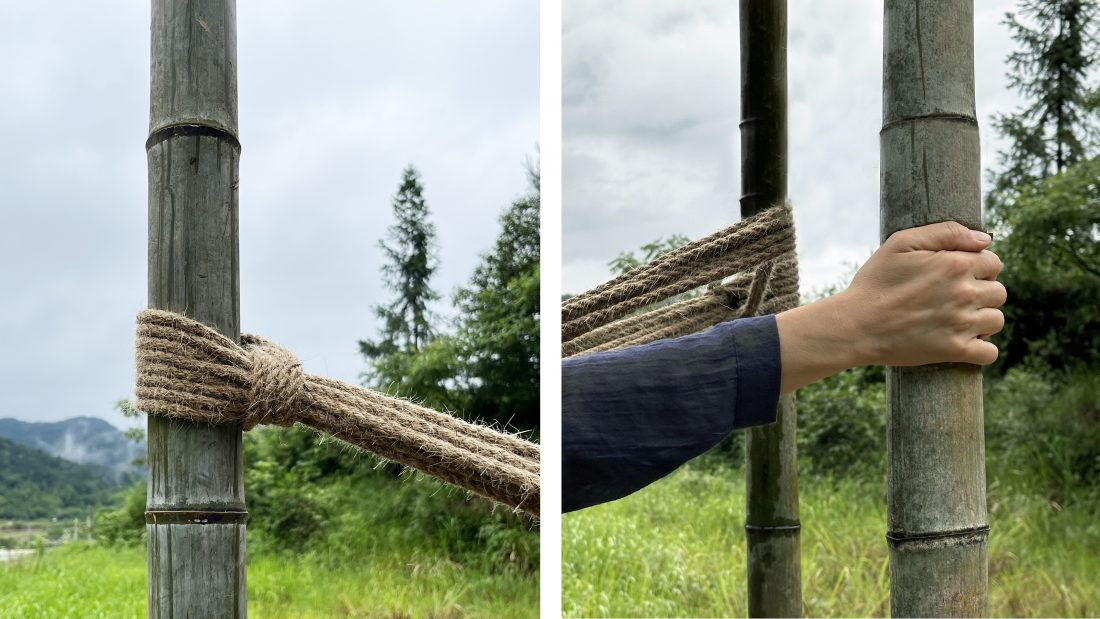

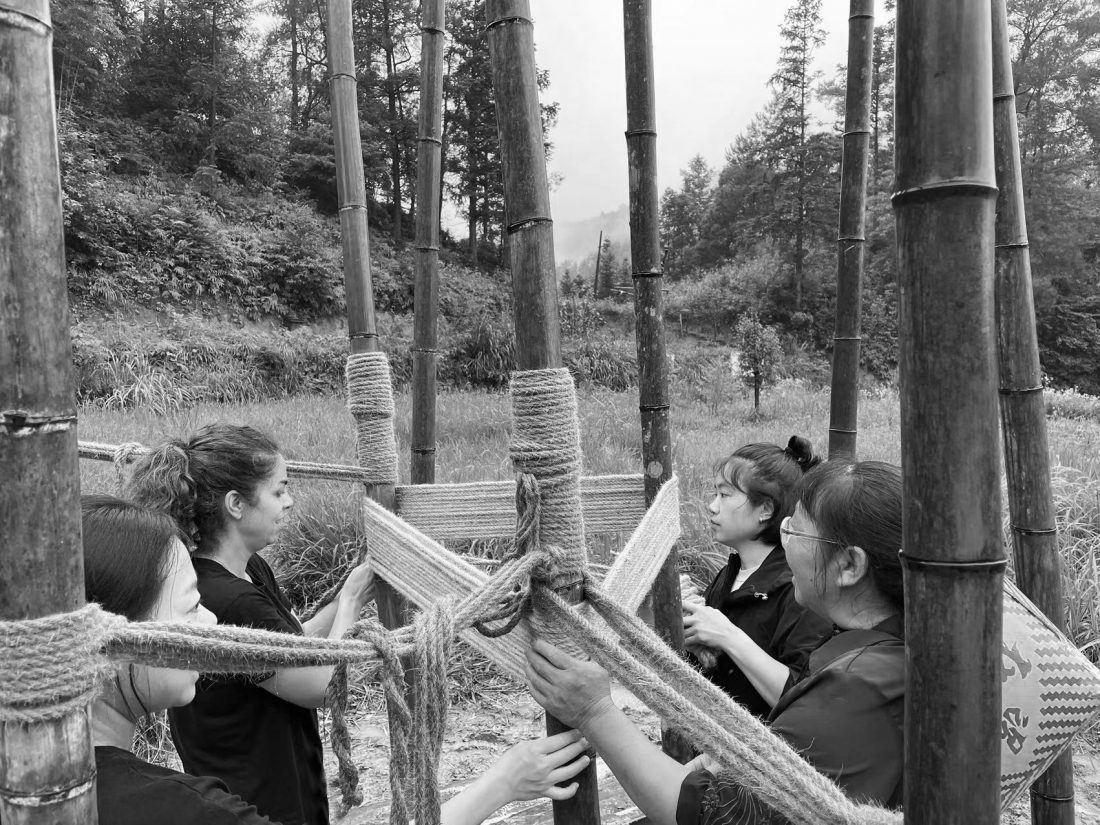

Situated southeast of the Lucitopia campus, at Zixi mountains, an open field surrounded by mountains was selected as the site. The installation is a figurative portrayal of a desire for reunion with the trees. It is a unit consisting of a core that encloses three adjacent trees in a hollow. The core is surrounded by other trees, and the enclosure represents 3 humans embracing each other (image 4,6,7). As a soft and organic material, the woven string imitates human movements. Translating the form of tree branches into humans’ hands, each tree is connected to its adjacent trees through dual strings. From one point, the work displays a figurative feature of a group of three people holding, relating and connecting to their immediate settings, the trees. From another point, the structure and form of the installation represent the presence of a constructed tree within the setting.

The work was designed through experimental steps before execution. The geometry of the form, joints, and the connection of the strings between the trunks were tested in several physical models in different scales (image 8-10). All models were crafted using fresh bamboo from the site. However, as a site-driven process, the executed work adopted improvised revisions on-site. The design articulation of the main elements follows the form of the bamboo branches. A “V shape” wing, which starts directly from the main trunk of the bamboo tree, is taken as a primary element that is branched and replicated in the work (image 11). This configuration tends to recall the figurative posture of a human embracing the trees. (image 14)

Construction:

“A Performance on Human Interaction with Trees”

Phase 1. Preparation and enabling the land

The site was on the hilly part of the Lucitopia campus, with land covered by wild grasses. The first step was to transplant 9 bamboo trees as the core of the installation and it required enabling work and land preparation. A group of young volunteers who were working at Lucitopia gathered to work at site. From the process of transferring the bamboo trees to the hill and removal of the grass and preparation of the land, up to transplanting the trees took few days and many different people alternatively collaborated in different parts. Looking at the snapshots from this process, I found outstanding moments in which everyone performed a scene as if it was part of a scripts.

Phase 2: Assembly of the strings

Several people voluntarily collaborated in this project to construct the installation. Standing among the planted trees, each person helped cover the core by carefully winding the woven strings around the trunks. Despite the regular rainfall and unpleasant weather condition, the act seemed like a deliberate and contemplative ritual as everyone was engaged with in an interaction with a tree.

The significance of this installation is not only for its conceptual expression of an unseen human desire to relate to nature but also for the physical memorial of those who acted within this land and the trees to create this work.

The work is a conceptual composition demonstrating human affinity with nature. This portrait of humans embracing their surrounding nature attempts to recall human empathy and identification with non-human natural elements, such as plants and ecosystems, as a key in human culture to protect and preserve the environment.

References:

- Naess, A. (1987). Self-realization: An ecological approach to being in the world. The Trumpeter, 4, 35–42

- Bragg, E. A. (1996). Towards ecological self: Deep ecology meets constructionist self-theory. Journal of Environmental Psychology

- Leopold, A. (1966). A Sand County almanac: With other essays on conservation from Round River’. Oxford: Oxford University Press

Related Information

Mona Azadian

Mona Azadian is an Iranian/Hungarian architect, educator, and garden designer. She is an assistant professor at the Department of Architecture at Xian Jiaotong Liverpool University (XJTLU) in Suzhou, China. Her work reflects the significance of “understanding the context” in contemporary design and developments. Focusing on natural and cultural contexts, she has worked in biophilic design, ecological landscape design, and adaptive-reuse architecture.

Her practice in garden design, titled ‘Untold Gardens,’ is an attempt to present authentic solutions to the demands of landscapes and gardens in arid cities, which shaped several gardens in the United Arab Emirates. The gardens balance the user’s needs and the aesthetic of the indigenous elements, emphasising the goal to increase water-use efficiency and climate adaptability.

Her work recalls the need to foster pro-environmental behaviours in response to current ecological degradation and mismanagement of natural resources. At the same time, she questions whether the higher policymakers’ sustainable guidelines and approaches are sufficient to address this matter. She credits the internal affinity for nature, which is rooted in human culture, as the key to applying sustainable approaches. She attempts to show how human empathy and identification with non-human natural elements are essential keys to enabling environment-supportive acts.