If the trees can talk

C-PLATFORM × Edwina fitzPatrick

Project Description

Archive of the trees.

The poet, W.H. Auden wrote ‘A culture is no better than its woods’. ‘The archive of the trees’ (www.archiveofthetrees.co.uk) commissioned by Fermynwood Contemporary Arts (http://fermynwoods.org), and funded by Arts Council England, tested this idea.

The residency took place in Fineshade Wood, Northamptonshire, in the United Kingdom (UK). It is partially ancient woodland (the remnant of the much larger ancient Rockingham Forest) and partially a tree farm, owned by the UK’s Forestry Commission since 1922. Some of the trees are over 600 years old, others are less than 50.

The six-month residency explored whether there was common ground in the way that the trees and humans responded to both ‘naturally’ changing seasons and ‘un-natural’ climate change and extreme weather. Curiously, the project coincided with one of England’s coldest winters and hottest summers on record, so there was plenty to talk about.

The project deliberately combined scientific data with anecdotal responses to weather and climate change. Edwina collaborating with Swansea’s University’s geography department, took small samples in Fineshade Wood (approximately 1 cm x 30cm) from different species of mature trees, which were then dried out, scanned and analysed. These images gave detailed information about which months each tree grew well, and which ones it didn’t. The analyses measured the tree’s xylem: its vascular tissue. In trees, xylem builds another ring of new xylem around itself. Dead xylem becomes heartwood, which acts as the tree’s backbone. The newer xylem (the sapwood) serves as the tree’s plumbing system.

This was then mapped against weather data from the UK Meteorological Office, news reports and local history archives. For example, every sampled tree grew very little over the summer of 1976 – it was one of the hottest and driest summers since records began in 1659. Yet, not all trees suffered from the freezing cold winter of 1962/3. The species native to colder regions grew much better than the native oaks.

Edwina also interviewed 60 people – a combination of foresters, forest residents, local historians and visitors – asking everyone the same questions about their experiences of weather. One of the first questions that she asked was “What is your first memory of weather?”, as she suspected that beautiful sunny days or cold/stormy/snowy conditions tend to stick in our mind.

Certain key themes emerged through the interviews and analyses of the tree cores: pollution; extreme weather; how introduced species (human or tree) adapted to their new environment; seasonality; extreme weather; the complexity of biodiversity; water (too much or not enough); recovery and healing; and the Wood itself. Others were human-centric such as weather prediction; tree management; and memories of weather.

The comments were combined with the enlarged images of the tree scans in two ways: between July and December 2018, the prints were wrapped around eleven of the cored trees to create a trail around Fineshade Wood. Some were in prominent places that most of the 120,000 annual visitors were likely to encounter. Others were in more remote areas that residents and regular visitors tended to frequent. The digital prints on canvas were waterproofed and attached simply by press studs. They could have easily been removed, but only one suffered any ‘damage’, which was children’s drawings. They generated a huge amount of interest, and Edwina was delighted to see visitors taking a lot of time to read each of the comments. Between September and December, they were also shown in the Arches gallery space at the entrance to the Wood as two-sided vertical prints. One side was the cored trees external bark (as though walking through a forest), the other side revealed its interior with the interview narratives superimposed on the core image.

The project’s outcomes were complex and sometimes unexpected.

1. The participants and visitors seemed amazed by the uniqueness and beauty of each tree core. Seeing the inside of a living tree, and how it responded to external stresses, created empathy with a non-human entity. This may also explain the lack of vandalism.

2. There was positive feedback that each participant’s year of birth was included in the text narrative, making the point that trees are around much long than we humans.

3. There were many discussions about how we remember weather, particularly as children. Two weeks of sunshine may be remembered as a heatwave. There were also interesting discussions about how to discuss weather with young children and introduce them to the concept of climate change.

4. The project took place during the height of Brexit (the UK leaving the European Union). This has led to a sharp rise in racism, so it was not surprising that several foreign interviewees discussed their experience of being an immigrant. This was contrasted with how introduced tree species coped with the UK climate.

5. Discussing the weather is a powerful tool to discuss complex issues. (The English are well known for making “small talk” about the weather). Timothy Morton calls climate change an uncomprehendable “Hyperobject”, so discussing memories of weather opens up complex debates without alienating viewers and participants.

6. Combining scientific data with anecdotal evidence is a powerful tool to address difficult issues such as climate change

Arboreal Laboratory

Arboreal Laboratory was a two-year residency in King’s Wood in southern England Commissioned by Stour Valley Arts and funded by the Arts Council of England and the Esmee Fairbairn Trust.

The forest had been a royal hunting ground: the word forest means enclosure. Yet the edges of a forest are porous. It led Edwina to think about how being in dense woodland invited us to use other senses than vision to negotiate our way around. How did the resident animals negotiate this world? The residency took the form of a series of experiments/propositions into how we use our senses. There were experiments into how we see, which were provocations about just how little we notice things around us. Some of the experiment’s outcomes were presented in the Wood itself, but most were deliberately shown in an urban gallery context, in order to trans-locate a rural wood to the city.

The first proposition was about our sense of smell. We asked, ‘can we capture moments over the cycle of a year in scent?’ The philosopher Immanuel Kant pronounced smell as the most unimportant of the senses and unworthy of ‘civilisation’. Yet woodlands are deeply scented places, from the rich odour of the earth to seasonal bluebells. Would it be possible to recreate the smell of a woodland plant being touched by sunlight, for example? Edwina collaborated with Quest International, who sampled the odour of some of King’s Wood plants using a Headspace Analysis machine to replicate the plant’s scent without damaging it. The results of this were combined by a perfumer, Dominique Le Lievre.

The four scents replicated 4 specific moments across the seasons: 21 April 2003 at 11.14’10”: 20 September 2003 at 17.30’23”; 19 November 2003 at 08. 31’ 02” and 19 January 2004 at 15. 20’ 44”. These clear liquid perfumes were presented in large clear blown glass vessels on transparent Perspex plinths, with just a few drops at the bottom of each vessel scenting a metre-wide zone around it. The scent was activated by the viewer passing by, and the artworks played on what appears to be visible or invisible.

The second set of experiments related to sound. Edwina started by recording different bird songs across the seasons in order to create a hypothetical score of birdsongs over the cycle of a year. This involved researching when each migrant bird visited and included several adventures trying to record nocturnal birds such as Nightjars, which only visit the Wood for six weeks each summer.

There is a proverb that says that a bird does not sing because it has an answer, it sings because it has a song. It is more complex than that. Most birdsong (as opposed to bird calls) is produced by male birds in order to attract a mate or to protect its territory. Birds cannot sing when they are hungry and singing in a leafy forest requires a huge amount of energy to transmit the sound. Edwina discovered that whilst human hearing is at the same frequency as birds, theirs is more attuned to time, which suggests that what we hear as 3 seconds of song would come across as 20 seconds of song to them. She therefore stretched the bird sound recordings accordingly.

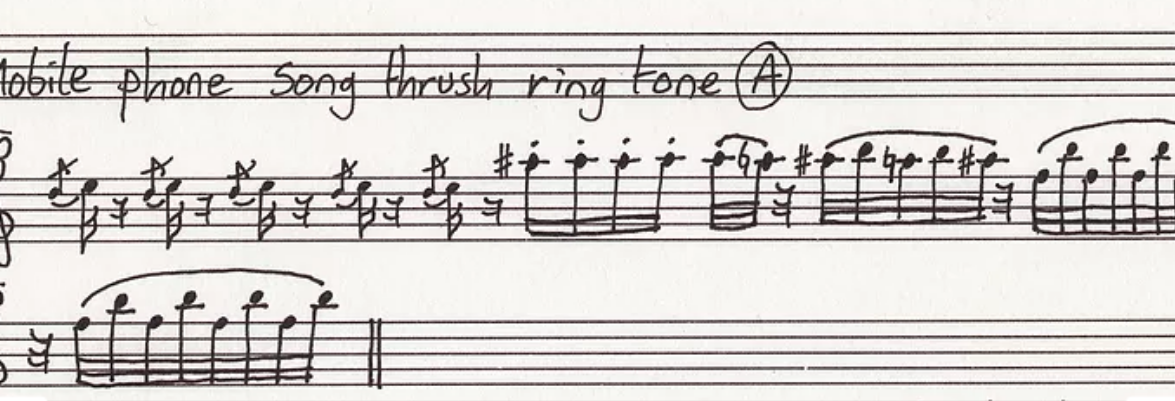

There was one final layer of sound involved. Small birds operate as in barometers of the overall health of an environment – the more there are, the healthier it is. At the time of the project, there was a lot of research into whether mobile phone masts were damaging bird populations. Edwina collaborated with composer, Matthew King, who created score for different species of bird calls and then replicated them on a (now outdated) mobile phone.

The real time, stretched and digital birdsongs were used in a three-screen video, called ‘Transpiration’.

Finally, there were experiments into time and space, celebrating how much Kings Wood changed over two seasonal cycle. There was one particular part of the forest that Edwina kept being drawn to. Initially, she considered making a permanent sited artwork there, but after a few months in residence this felt completely inappropriate. Given that ‘Arboreal Laboratory’ was about the invisible and layers of visibility, Edwina reflected what the least visible thing that she could permanently introduce to a forest might be. It was, of course, a tree. One of the video screens was of two humans dressed as red squirrels planting an apple tree. It was intended to stay there permanently, however the resident deer had other ideas and ate it.

Having worked with a composer, perfumers and chemical analysis scientists, the project reinforced how powerful and inspiring cross and inter disciplinary projects can be. It also confirmed that longer term residencies (1 year +) lead to more complex seasonal understandings of a space-place. It led to Edwina developing the strategy of field work as a central part of her art practice, which she has subsequently evolved into interactive fieldwork.

Related Information

Edwina fitzPatrick

Edwina fitzPatrick’s art project, the archive of the trees, happened in Fineshade Wood in Northamptonshire between January and December 2018. Edwina invited Swansea University’s UK Oak Project team to collect and analyse very small cores from healthy mature trees in Fineshade Wood – the samples didn’t harm the trees. The cores reveal the tree’s age, growing patterns, past weather conditions and stresses such as diseases. In effect, they are the tree’s own archive: each specimen reveals its ‘autobiography’.

Fineshade Wood is a remnant of the much larger ancient Rockingham Forest, so there is a long regional history of human and arboreal lives being intertwined. Edwina reflected this by inviting forest residents, foresters, local groups and Fineshade visitors to contribute their observations about both the Wood’s trees and unusual weather they’ve experienced in the area both now and spanning previous decades.

Article Credit ![]() Edwina fitzPatrick

Edwina fitzPatrick

Date

2019年1月18日

Category

Future Institute